By mid-morning on Christmas Day I’m usually ready to retreat from the fray to the quietest corner I can find with a book and a cup of tea. Though wasn’t much ‘fray’ today so I ought to have been entirely blissed out. However, I still felt the niggling need to hide myself a way for a bit at least. Even the energy in the air around this time can make me want to withdraw. I was also feeling distressed about the lack of Winter weather. (I’m experiencing this scary sense of déjà vu because I wrote something similar to this last year.)

There wasn’t a frost this morning. There hasn’t been a smattering of snow. It’s been unseasonably warm – the warmest Christmas Day since 2016 – with some half-hearted slaps of rain which I eyed hatefully through the kitchen window.

Christmas Eve was the warmest in over 20 years; I feel off when the weather is off. I feel disconnected and uncomfortable, anxious and pissed off, yes, pissed off, when there isn’t snow on the ground in late December. I’m equally as distressed now at 37 as I was at 7 about not having a white Christmas.

I spent Christmas in Iceland in 2021 and I still remember how wonderfully freezing it was, how aligned I felt with the season. I remember Christmases in Sweden and Winters in Norway and Canada where snow on snow on snow made me feel whole and happy.

Today, I spent less than a minute outside. I would have cried had I gone for a walk because there was no need for a coat, gloves, or a hat. I hauled this mountain of feelings aside for family because, of course. But it wasn’t easy. Today’s weather could have been any other day in the year in England.

I know that part of what I’m feeling is solastalgia. I’m pining for the Winters I used to know as a kid. As Nancy Campbell writes in the introduction to her book Nature Tales for Winter Nights ‘Solastalgia replaces nostalgia, when the snow scenes depicted on holiday cards are rarely seen in our neighbourhoods.’

December is supposed to be an enchanted month. Christmas Day is supposed to be especially enchanted, heaped with magick and snow. My daughter has felt the magick of the day. She hasn’t experienced any lack (that I know of) – Santa Claus ate the mince pie left out for him and Rudolf snaffled the carrot. Everything on her list was under the tree (mar one which the elves are still working on) and she eating chocolate in her pyjamas mid-afternoon.

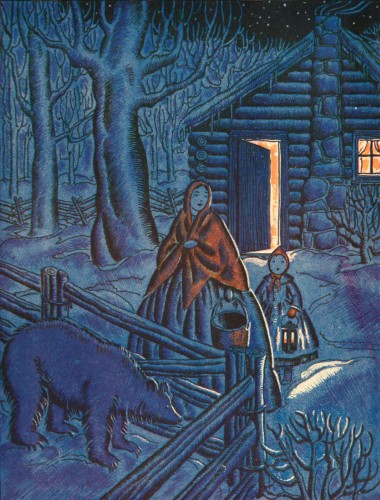

But the lack of Wintry weather has been bearing down on me. Throughout December, I’ve been thinking about the Wintry scenes in some of my favourite childhood stories, scenes from both books and their film adaptations that bonded with and which had kept a place in the unpredictable sea of my memory.

Though I believe I’ve been thinking about them more so this year, because of how rare a ‘true winter’ is becoming. They provide comfort in this crisis, when I am panicked about where Winter is going and if we can possibly encourage him back or if it’s too late.

Below are some extracts from books and scenes from their film adaptations that have nourished me since childhood. All three books are available to read for free online at Project Gutenberg. I hope they can nourish you too and that you can find, if you need, a little corner to retreat to. I also hope, more than anything, that its cold where you are and that the snow is thick enough to muffle the world.

Little House In The Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder

FROM THE CHAPTER WINTER DAYS AND WINTER NIGHTS

The first snow came, and the bitter cold. Every morning Pa took his gun and his traps and was gone all day in the Big Woods, setting the small traps for muskrats and mink along the creeks, the middle-sized traps for foxes and wolves in the woods. He set out the big bear traps hoping to get a fat bear before they all went into their dens for the winter.

One morning he came back, took the horses and sled, and hurried away again. He had shot a bear. Laura and Mary jumped up and down and clapped their hands, they were so glad. Mary shouted:

“I want the drumstick! I want the drumstick!”

Mary did not know how big a bear’s drumstick is.

When Pa came back he had both a bear and a pig in the wagon. He had been going through the woods, with a big bear trap in his hands and the gun on his shoulder, when he walked around a big pine tree covered with snow, and the bear was behind the tree.

The bear had just killed the pig and was picking it up to eat it. Pa said the bear was standing up on its hind legs, holding the pig in its paws just as though they were hands.

Pa shot the bear, and there was no way of knowing where the pig came from nor whose pig it was.

“So I just brought home the bacon,” Pa said.

There was plenty of fresh meat to last for a long time. The days and the nights were so cold that the pork in a box and the bear meat hanging in the little shed outside the back door were solidly frozen and did not thaw.

When Ma wanted fresh meat for dinner Pa took the ax and cut off a chunk of frozen bear meat or pork. But the sausage balls, or the salt pork, or the smoked hams and the venison, Ma could get for herself from the shed or the attic.

The snow kept coming till it was drifted and banked against the house. In the mornings the window panes were covered with frost in beautiful pictures of trees and flowers and fairies.

Ma said that Jack Frost came in the night and made the pictures, while everyone was asleep. Laura thought that Jack Frost was a little man all snowy white, wearing a glittering white pointed cap and soft white knee-boots made of deer-skin. His coat was white and his mittens were white, and he did not carry a gun on his back, but in his hands he had shining sharp tools with which he carved the pictures.

Laura and Mary were allowed to take Ma’s thimble and made pretty patterns of circles in the frost on the glass. But they never spoiled the pictures that Jack Frost had made in the night.

When they put their mouths close to the pane and blew their breath on it, the white frost melted and ran in drops down the glass. Then they could see the drifts of snow outdoors and the great trees standing bare and black, making thin blue shadows on the white snow.

From the chapter CHRISTMAS

Christmas was coming.

The little log house was almost buried in snow. Great drifts were banked against the walls and windows, and in the morning when Pa opened the door, there was a wall of snow as high as Laura’s head. Pa took the shovel and shoveled it away, and then he shoveled a path to the barn, where the horses and the cows were snug and warm in their stalls.

The days were clear and bright. Laura and Mary stood on chairs by the window and looked out across the glittering snow at the glittering trees. Snow was piled all along their bare, dark branches, and it sparkled in the sunshine. Icicles hung from the eaves of the house to the snowbanks, great icicles as large at the top as Laura’s arm. They were like glass and full of sharp lights.

Pa’s breath hung in the air like smoke, when he came along the path from the barn. He breathed it out in clouds and it froze in white frost on his mustache and beard.

When he came in, stamping the snow from his boots, and caught Laura up in a bear’s hug against his cold, big coat, his mustache was beaded with little drops of melting frost.

***

Ma was busy all day long, cooking good things for Christmas. She baked salt-rising bread and rye ‘n Injun bread, and Swedish crackers, and a huge pan of baked beans, with salt pork and molasses. She baked vinegar pies and dried-apple pies, and filled a big jar with cookies, and she let Laura and Mary lick the cake spoon.

FROM THE CHAPTER COATS AND MUFFLERS AND VEILS AND SHAWLS

One morning she boiled molasses and sugar together until they made a thick syrup, and Pa brought in two pans of clean, white snow from outdoors. Laura and Mary each had a pan, and Pa and Ma showed them how to pour the dark syrup in little streams on to the snow.

They made circles, and curlicues, and squiggledy things, and these hardened at once and were candy. Laura and Mary might eat one piece each, but the rest was saved for Christmas Day.

The Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Grahame

FROM THE CHAPTER THE WILD WOOD

There was plenty to talk about on those short winter days when the animals found themselves round the fire; still, the Mole had a good deal of spare time on his hands, and so one afternoon, when the Rat in his arm-chair before the blaze was alternately dozing and trying over rhymes that wouldn’t fit, he formed the resolution to go out by himself and explore the Wild Wood, and perhaps strike up an acquaintance with Mr. Badger.

It was a cold still afternoon with a hard steely sky overhead, when he slipped out of the warm parlour into the open air. The country lay bare and entirely leafless around him, and he thought that he had never seen so far and so intimately into the insides of things as on that winter day when Nature was deep in her annual slumber and seemed to have kicked the clothes off. Copses, dells, quarries and all hidden places, which had been mysterious mines for exploration in leafy summer, now exposed themselves and their secrets pathetically, and seemed to ask him to overlook their shabby poverty for a while, till they could riot in rich masquerade as before, and trick and entice him with the old deceptions. It was pitiful in a way, and yet cheering—even exhilarating. He was glad that he liked the country undecorated, hard, and stripped of its finery. He had got down to the bare bones of it, and they were fine and strong and simple. He did not want the warm clover and the play of seeding grasses; the screens of quickset, the billowy drapery of beech and elm seemed best away; and with great cheerfulness of spirit he pushed on towards the Wild Wood, which lay before him low and threatening, like a black reef in some still southern sea.

There was nothing to alarm him at first entry. Twigs crackled under his feet, logs tripped him, funguses on stumps resembled caricatures, and startled him for the moment by their likeness to something familiar and far away; but that was all fun, and exciting. It led him on, and he penetrated to where the light was less, and trees crouched nearer and nearer, and holes made ugly mouths at him on either side.

Everything was very still now. The dusk advanced on him steadily, rapidly, gathering in behind and before; and the light seemed to be draining away like flood-water.

Then the faces began.

It was over his shoulder, and indistinctly, that he first thought he saw a face; a little evil wedge-shaped face, looking out at him from a hole. When he turned and confronted it, the thing had vanished.

He quickened his pace, telling himself cheerfully not to begin imagining things, or there would be simply no end to it. He passed another hole, and another, and another; and then—yes!—no!—yes! certainly a little narrow face, with hard eyes, had flashed up for an instant from a hole, and was gone. He hesitated—braced himself up for an effort and strode on. Then suddenly, and as if it had been so all the time, every hole, far and near, and there were hundreds of them, seemed to possess its face, coming and going rapidly, all fixing on him glances of malice and hatred: all hard-eyed and evil and sharp.

If he could only get away from the holes in the banks, he thought, there would be no more faces. He swung off the path and plunged into the untrodden places of the wood.

Then the whistling began.

Very faint and shrill it was, and far behind him, when first he heard it; but somehow it made him hurry forward. Then, still very faint and shrill, it sounded far ahead of him, and made him hesitate and want to go back. As he halted in indecision it broke out on either side, and seemed to be caught up and passed on throughout the whole length of the wood to its farthest limit. They were up and alert and ready, evidently, whoever they were! And he—he was alone, and unarmed, and far from any help; and the night was closing in.

Then the pattering began.

He thought it was only falling leaves at first, so slight and delicate was the sound of it. Then as it grew it took a regular rhythm, and he knew it for nothing else but the pat-pat-pat of little feet still a very long way off. Was it in front or behind? It seemed to be first one, and then the other, then both. It grew and it multiplied, till from every quarter as he listened anxiously, leaning this way and that, it seemed to be closing in on him. As he stood still to hearken, a rabbit came running hard towards him through the trees. He waited, expecting it to slacken pace, or to swerve from him into a different course. Instead, the animal almost brushed him as it dashed past, his face set and hard, his eyes staring. “Get out of this, you fool, get out!” the Mole heard him mutter as he swung round a stump and disappeared down a friendly burrow.

The pattering increased till it sounded like sudden hail on the dry leaf-carpet spread around him. The whole wood seemed running now, running hard, hunting, chasing, closing in round something or—somebody? In panic, he began to run too, aimlessly, he knew not whither. He ran up against things, he fell over things and into things, he darted under things and dodged round things. At last he took refuge in the deep dark hollow of an old beech tree, which offered shelter, concealment—perhaps even safety, but who could tell? Anyhow, he was too tired to run any further, and could only snuggle down into the dry leaves which had drifted into the hollow and hope he was safe for a time. And as he lay there panting and trembling, and listened to the whistlings and the patterings outside, he knew it at last, in all its fullness, that dread thing which other little dwellers in field and hedgerow had encountered here, and known as their darkest moment—that thing which the Rat had vainly tried to shield him from—the Terror of the Wild Wood!

From later on in the chapter after Ratty has found the Mole in The Wild Wood

“What’s up, Ratty?” asked the Mole.

“Snow is up,” replied the Rat briefly; “or rather, down. It’s snowing hard.”

The Mole came and crouched beside him, and, looking out, saw the wood that had been so dreadful to him in quite a changed aspect. Holes, hollows, pools, pitfalls, and other black menaces to the wayfarer were vanishing fast, and a gleaming carpet of faery was springing up everywhere, that looked too delicate to be trodden upon by rough feet. A fine powder filled the air and caressed the cheek with a tingle in its touch, and the black boles of the trees showed up in a light that seemed to come from below.

“Well, well, it can’t be helped,” said the Rat, after pondering. “We must make a start, and take our chance, I suppose. The worst of it is, I don’t exactly know where we are. And now this snow makes everything look so very different.”

It did indeed. The Mole would not have known that it was the same wood. However, they set out bravely, and took the line that seemed most promising, holding on to each other and pretending with invincible cheerfulness that they recognised an old friend in every fresh tree that grimly and silently greeted them, or saw openings, gaps, or paths with a familiar turn in them, in the monotony of white space and black tree-trunks that refused to vary.

An hour or two later—they had lost all count of time—they pulled up, dispirited, weary, and hopelessly at sea, and sat down on a fallen tree-trunk to recover their breath and consider what was to be done. They were aching with fatigue and bruised with tumbles; they had fallen into several holes and got wet through; the snow was getting so deep that they could hardly drag their little legs through it, and the trees were thicker and more like each other than ever. There seemed to be no end to this wood, and no beginning, and no difference in it, and, worst of all, no way out.

“We can’t sit here very long,” said the Rat. “We shall have to make another push for it, and do something or other. The cold is too awful for anything, and the snow will soon be too deep for us to wade through.” He peered about him and considered. “Look here,” he went on, “this is what occurs to me. There’s a sort of dell down here in front of us, where the ground seems all hilly and humpy and hummocky. We’ll make our way down into that, and try and find some sort of shelter, a cave or hole with a dry floor to it, out of the snow and the wind, and there we’ll have a good rest before we try again, for we’re both of us pretty dead beat. Besides, the snow may leave off, or something may turn up.”

So once more they got on their feet, and struggled down into the dell, where they hunted about for a cave or some corner that was dry and a protection from the keen wind and the whirling snow. They were investigating one of the hummocky bits the Rat had spoken of, when suddenly the Mole tripped up and fell forward on his face with a squeal.

“O my leg!” he cried. “O my poor shin!” and he sat up on the snow and nursed his leg in both his front paws.

“Poor old Mole!” said the Rat kindly. “You don’t seem to be having much luck to-day, do you? Let’s have a look at the leg. Yes,” he went on, going down on his knees to look, “you’ve cut your shin, sure enough. Wait till I get at my handkerchief, and I’ll tie it up for you.”

“I must have tripped over a hidden branch or a stump,” said the Mole miserably. “O, my! O, my!”

“It’s a very clean cut,” said the Rat, examining it again attentively. “That was never done by a branch or a stump. Looks as if it was made by a sharp edge of something in metal. Funny!” He pondered awhile, and examined the humps and slopes that surrounded them.

“Well, never mind what done it,” said the Mole, forgetting his grammar in his pain. “It hurts just the same, whatever done it.”

But the Rat, after carefully tying up the leg with his handkerchief, had left him and was busy scraping in the snow. He scratched and shovelled and explored, all four legs working busily, while the Mole waited impatiently, remarking at intervals, “O, come on, Rat!”

Suddenly the Rat cried “Hooray!” and then “Hooray-oo-ray-oo-ray-oo-ray!” and fell to executing a feeble jig in the snow.

“What have you found, Ratty?” asked the Mole, still nursing his leg.

“Come and see!” said the delighted Rat, as he jigged on.

The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis

FROM THE CHAPTER LUCY LOOKS INTO A WARDROBE

There was nothing Lucy liked so much as the smell and feel of fur. She immediately stepped into the wardrobe and got in among the coats and rubbed her face against them, leaving the door open, of course, because she knew that it is very foolish to shut oneself into any wardrobe. Soon she went further in and found that there was a second row of coats hanging up behind the first one. It was almost quite dark in there and she kept her arms stretched out in front of her so as not to bump her face into the back of the wardrobe. She took a step further in—then two or three steps—always expecting to feel woodwork against the tips of her fingers. But she could not feel it.

“This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!” thought Lucy, going still further in and pushing the soft folds of the coats aside to make room for her. Then she noticed that there was something crunching under her feet. “I wonder is that more moth-balls?” she thought, stooping down to feel it with her hands. But instead of feeling the hard, smooth wood of the floor of the wardrobe, she felt something soft and powdery and extremely cold, “This is very queer,” she said, and went on a step or two further.

Next moment she found that what was rubbing against her face and hands was no longer soft fur but something hard and rough and even prickly. “Why, it is just like branches of trees!” exclaimed Lucy. And then she saw that there was a light ahead of her; not a few inches away where the back of the wardrobe ought to have been, but a long way off. Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found that she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

Lucy felt a little frightened, but she felt very inquisitive and excited as well. She looked back over her shoulder and there, between the dark tree-trunks, she could still see the open doorway of the wardrobe and even catch a glimpse of the empty room from which she had set out. (She had, of course, left the door open, for she knew that it is a very silly thing to shut oneself into a wardrobe.) It seemed to be still daylight there. “I can always get back if anything goes wrong,” thought Lucy. She began to walk forward, crunch-crunch, over the snow and through the wood towards the other light.

In about ten minutes she reached it and found that it was a lamp-post. As she stood looking at it, wondering why there was a lamp-post in the middle of a wood and wondering what to do next, she heard a pitter patter of feet coming towards her. And soon after that a very strange person stepped out from among the trees into the light of the lamp-post.

He was only a little taller than Lucy herself and he carried over his head an umbrella, white with snow. From the waist upwards he was like a man, but his legs were shaped like a goat’s (the hair on them was glossy black) and instead of feet he had goat’s hoofs. He also had a tail, but Lucy did not notice this at first because it was neatly caught up over the arm that held the umbrella so as to keep it from trailing in the snow. He had a red woollen muffler round his neck and his skin was rather reddish too. He had a strange, but pleasant little face with a short pointed beard and curly hair, and out of the hair there stuck two horns, one on each side of his forehead. One of his hands, as I have said, held the umbrella: in the other arm he carried several brown paper parcels. What with the parcels and the snow it looked just as if he had been doing his Christmas shopping. He was a Faun. And when he saw Lucy he gave such a start of surprise that he dropped all his parcels.

“Goodness gracious me!” exclaimed the Faun.

FROM THE CHAPTER EDMUND AND THE WARDROBE

“Lucy! Lucy! I’m here too—Edmund.”

There was no answer.

“She’s angry about all the things I’ve been saying lately,” thought Edmund. And though he did not like to admit that he had been wrong, he also did not much like being alone in this strange, cold, quiet place; so he shouted again.

“I say, Lu! I’m sorry I didn’t believe you. I see now you were right all along. Do come out. Make it Pax.”

Still there was no answer.

“Just like a girl,” said Edmund to himself, “sulking somewhere, and won’t accept an apology.” He looked round him again and decided he did not much like this place, and had almost made up his mind to go home, when he heard, very far off in the wood, a sound of bells. He listened and the sound came nearer and nearer and at last there swept into sight a sledge drawn by two reindeer.

The reindeer were about the size of Shetland ponies and their hair was so white that even the snow hardly looked white compared with them; their branching horns were gilded and shone like something on fire when the sunrise caught them. Their harness was of scarlet leather and covered with bells. On the sledge, driving the reindeer, sat a fat dwarf who would have been about three feet high if he had been standing. He was dressed in polar bear’s fur and on his head he wore a red hood with a long gold tassel hanging down from its point; his huge beard covered his knees and served him instead of a rug. But behind him, on a much higher seat in the middle of the sledge sat a very different person—a great lady, taller than any woman that Edmund had ever seen. She also was covered in white fur up to her throat and held a long straight golden wand in her right hand and wore a golden crown on her head. Her face was white—not merely pale, but white like snow or paper or icing sugar, except for her very red mouth. It was a beautiful face in other respects, but proud and cold and stern.

The sledge was a fine sight as it came sweeping towards Edmund with the bells jingling and the Dwarf cracking his whip and the snow flying up on each side of it.

“Stop!” said the Lady, and the Dwarf pulled the reindeer up so sharp that they almost sat down. Then they recovered themselves and stood champing their bits and blowing. In the frosty air the breath coming out of their nostrils looked like smoke.

“And what, pray, are you?” said the Lady, looking hard at Edmund.

“I’m—I’m—my name’s Edmund,” said Edmund rather awkwardly. He did not like the way she looked at him.

The Lady frowned. “Is that how you address a Queen?” she asked, looking sterner than ever.

“I beg your pardon, your Majesty, I didn’t know,” said Edmund.

“Not know the Queen of Narnia?” cried she. “Ha! You shall know us better hereafter. But I repeat—what are you?”